WOLDWINITE WEDNESDAY proudly welcomes back NJ Mastro in her continuing biography of Mary Wollstonecraft!

Mary Wollstonecraft: The First of a New Genus by NJ Mastro

Part II: An introduction to Mary Wollstonecraft.

In August 1787, Mary Wollstonecraft traveled by coach from Bristol to London with one purpose in mind: to earn a living as a writer. Her situation was dire; she’d just been fired from her job as a governess for her progressive views regarding girls’ education, leaving her homeless. But Mary had something money couldn’t buy: a supreme confidence in her ability to make her own way. A sworn spinster, she had only herself on whom to rely. All she needed was a chance to show the world what she could do.

The person who gave her that chance was her publisher, Joseph Johnson. The year prior, Johnson had purchased Mary’s first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, before she had even finished it, promising to publish anything else she wrote. One of London’s most successful publishers and known for printing works that pushed the boundaries of accepted thought, Johnson recognized a fellow rebel when he saw one. When Mary showed up unexpectedly at No. 75 St. Paul’s Churchyard a year later, she delivered him a manuscript. Mary, A Fiction was her first novel and was not a story about Mary, as the name would suggest. But the narrative contained endless biographical elements.

Joseph Johnson, a confirmed bachelor in his fifties, welcomed Mary and insisted she stay with him until he could find a house for her to rent. Johnson’s living quarters were above his print shop. Mary accepted, a bold move for a single, unchaperoned woman. She was broke, however, and by then, she was 28 and used to breaking the rules. In all, she would spend three weeks at his house.

While at Johnson’s Mary attended weekly dinners for which he was famous. Twice a week, he invited a smattering of friends to a dinner of simple fare. Talk of politics, the arts, religion, medicine—no topic was off limits—was always spirited. Johnson’s Circle, as the mix of friends was called, proved a fertile environment for Mary to advance her intellect and sharpen her political views. Among Johnson’s guests were members of London’s literati, thought leaders like Thomas Holcroft, William Blake, John Bonnycastle, George Fordyce, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Joseph Priestly. Sarah Trimmer, Maria Edgeworth, and Anna Barbauld were frequent guests as well.

While Johnson looked for a house for Mary to rent, she visited her sisters Everina and Bess in Henley and Market Harborough, respectively. Both sisters wanted to live with Mary, but she refused knowing she had all she could do to take care of herself. And Mary didn’t tell them she intended to become a writer; she only promised to send them money when she was back on her feet.

Mary held good on her promise. When she returned from Market Harborough, she moved into a house of her own, started drafting her third book, translated works for Johnson, and began writing reviews for a new progressive periodical he was starting with Thomas Christie, a journalist from Scotland. “I am then going to be the first of a new genus—I tremble at the attempt yet if I fail—I only suffer…” she wrote to Everina in November, a sign that Mary wanted to be a different kind of woman writer.

Mary’s writing career would soar under Johnson’s wing, yet there are two sides to an individual, the professional and the personal. When she declared her spinsterhood all those years ago, this spirited woman hadn’t considered how she would respond to longings within. Despite her best efforts to keep men at a distance, Mary was as susceptible to falling in love as any human being. Before William Godwin, two other men would occupy her thoughts for nearly a decade. Neither would impede her trajectory as a writer, but pining over one of them would send her to Revolutionary France; loving the other one would almost kill her.

The first man to throw Mary off her single game was Henry Fuseli, an artist she met at Johnson’s table. By early 1788, Mary had published her second and third books. Mary, A Fiction and Original Stories from Real Life, a set of tales intended to teach valuable moral lessons, sat alongside Thoughts on the Education of Daughters in Johnson’s display window of his bookshop. Fuseli, meanwhile, was embedding himself at the relatively new Royal Academy of Arts.

The two were intrigued by each other’s brilliance. Mary, who had read widely and had been mentored by men who had groomed her precocity, was one of few women who could converse intellectually with men. The highly educated Fuseli charmed her with his knowledge and wit. Together with Johnson, they would spend evenings engaged in philosophical and political debate.

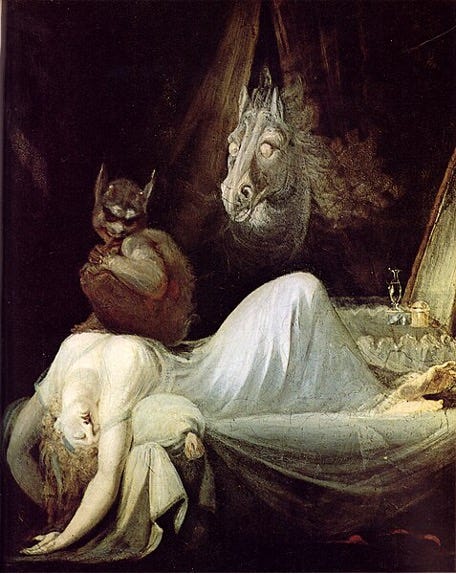

Mary and Fuseli also shared a kindred spirit. They were both passionate, outspoken individuals. Fuseli’s paintings were as emotionally charged as Mary’s writings. They differed, however, in the nature of their obsessions. Mary's focus was on seeking justice and liberty for the masses, and most notably, women and girls; Fuseli was fascinated by dark, fantastical themes. Through his art, he explored the supernatural. Over Johnson’s dining table hung an early rendition of “The Nightmare,” one of Fuseli’s most famous paintings.

The French Revolution was also getting underway just as Mary and Fuseli met. From afar, Johnson’s Circle observed democracy unfolding close to home this time instead of across the Atlantic. All were anti-monarchist, supported the Commoners, and wanted to see reform in England. From his printing presses, Johnson stoked the flame of change by publishing books and articles in support of the French rebels. He even hired Mary and Fuseli to translate political pamphlets coming out of France for his Analytical Review.

Then in 1789, Edmund Burke, a powerful conservative Member of Parliament, wrote a scathing criticism of the Revolution. Mary responded by writing A Declaration of the Rights of Men, which you can read about here in Part I of Mary’s introduction in Litcuzzwords. The pamphlet marked Mary’s entry into polemical works.

Two years later, Mary wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, her political treatise on the state of affairs for women. "Contending for the rights of women, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge, for truth must be common to all…”

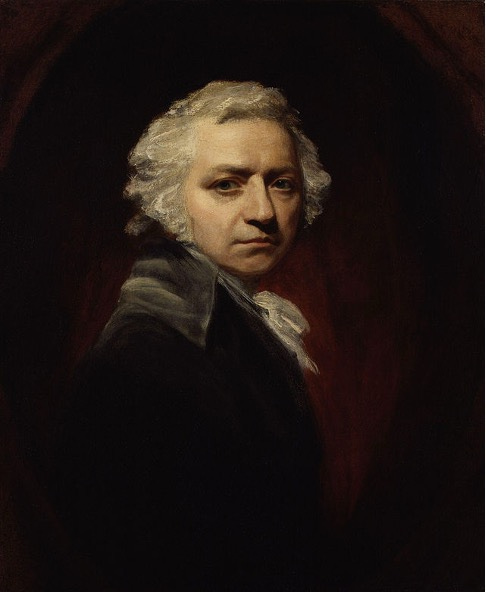

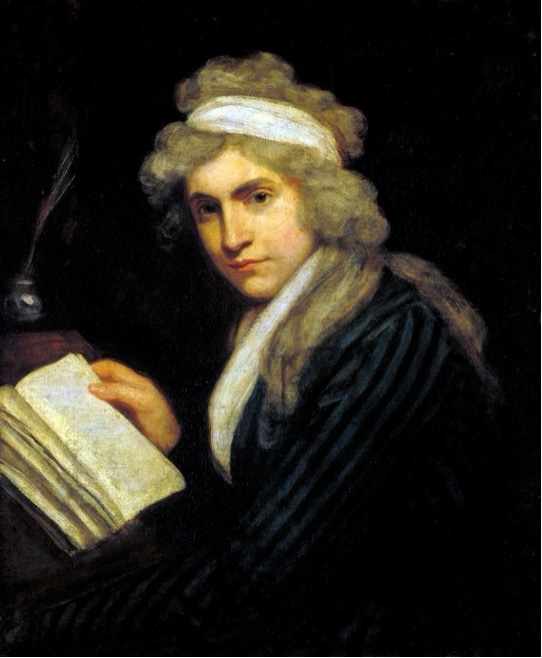

The book advocated for girls’ education and more opportunities for women. It became an instant international best seller, placing Mary alongside other radical philosophers of her time, including Thomas Paine, William Blake, Catharine Macaulay, and Helen Maria Williams. Translations were soon underway in German and French as crates of books were being shipped to America, where then vice-president John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams read it. Abigail sided with Mary and called herself “Wollstonecraft’s pupil.” John Adams thought Mary wildly radical. (Below: A painting of Mary by artist John Opie, 1790)

Mary’s success, however, was followed by a low period in her life. She struggled with episodes of depression, and after A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she seems to have fallen into an emotional abyss. She wrote nothing of substance other than her articles for the Analytical Review. Biographers speculate that her down mood had much to do with her growing feelings for Henry Fuseli, who was a married man.

Based on fragments of letters she wrote to Fuseli, it’s as if Mary sought to form an intellectual union with him, a merging of minds. It was all she could hope for. Mary would never have considered adultery. She was too pious, and it went against her rational judgment. But she was willing to suggest to the Fuselis that she move in with them. They spent a great deal of time together, and it was common at the time for people to share a household. Fuseli’s wife, Sophia, felt Mary had overstepped. Henry turned on Mary, and the couple accused her of suggesting a ménage à trois. Humiliated, Mary moved to Paris, where she would write about the Revolution in a series of letter for Joseph Johnson to publish in the Analytical Review.

Next week: To Paris and Back Again and a Life Cut Short. Thanks so much NJ!